Fernando Filipe Paulos Vieira1, Francisco Lotufo Neto2

1 PhD in Clinical Psychology at University of São Paulo, Brazil.

2 Associate Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry of University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Received: 20 July 2024

Revised: 24 July 2024

Accepted: 24 July 2024

Published: 24 July 2024

Corresponding author:

Fernando Filipe Paulos Vieira

PhD in Clinical Psychology at University of São Paulo, Brazil. fernando.paulos@usp.br

Cite as:

| Paulos Vieira FF, Lotufo Neto F. The Impact of a Strong Pain in the Chest for the Diagnosis of Depression or Anxiety Acta Med Eur. 2024;6(4):7-15. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.12807558 |

doi: 10.5281/zenodo.12807558

ABSTRACT

| This research aimed to investigate differences between patients with and without anguish in terms of symptomatology and comorbidities and to find out whether patients with depression and with anxiety have more anguish than patients who do not have depression and anxiety. For this purpose, a statistical analysis was carried out, which included a descriptive analysis that followed the verification of the distributions of the variables of the questionnaires in the groups, and an inferential analysis in which it was the dimension of some questionnaires was reduced and latent variables were constructed, possibly more discriminative in relation to the groups, and the variables with the greatest predictive power for anguish were identified. According to the results, the variables that most showed relationships with anguish were the following: Gender, Reduced Hamilton Score, BSI Somatization, Age and MINI Depression. |

Keywords:

Anguish, precordial pain, depression, anxiety, psychopathology.

INTRODUCTION

Many times, human beings are struck by a strange feeling of emptiness, an intense malaise, a deep restlessness that causes them to feel oppression in the chest, a tightness in the chest and the impression that they are being suffocated. In itself, the term anguish has a high weight, since its synonyms are agony, affliction, torment, martyrdom, torture, which leads to the feeling of oppression, emptiness, hole, sword, pain, compression that can present intensity high, however it is not considered pathological (1). Currently, the floods caused by torrential rains in southern Brazil have created a strong feeling of anguish among the population.

The origin of the word anguish goes back to the Latin verb angere, which has the meaning of squeezing, compressing (especially the throat), strangling, choking, suffocating; from the Greek term “koinê or coine” which means to squeeze, strangle; from the Indo-Germanic ‘angh’ which means tight, painfully contracted; from the ancient Egyptian ‘anj’, ‘ankh’ or ‘ank’ which means cross with wings or Egyptian cross and which gives rise to ‘angor’ which, in turn, gives the notion of narrowing (2).

In the scientific field, anguish arose when the German word angst was inserted by Sigmund Freud. However, when translating Freudian works into English, James Beaumont Strachey translated the word angst into anxiety, to obtain better acceptance in psychiatric circles. The justification for such a translation was that “angst” was a term commonly used in German and could be translated by some equally common English words, such as “fear”, “fright”, “alarm”. Thus, he concluded that the adopted word “’anxiety’ would also have a common meaning in everyday use, with only a remote connection with any of the uses of the German ‘angst” and that it would be “impractical” to settle on a single English term as a translation. exclusive, but that there would be a use already established by psychiatry that would justify the choice of the term “anxiety” (3).

Gentil and Gentil (2009), within the scope of an investigation into brain function, hypothesized that anguish could have clinical and neurobiological relevance, that is, the authors defended the hypothesis that the feeling of tightness or oppression located in the thoracic region could have an emotional connection.

Over the last few decades, conceptual confusion has been observed when approaching concepts such as fear, panic, anxiety and anguish. The feeling of anguish, which focuses on events occurring in the present moment, is accompanied by sensations in the thoracic region that can present themselves in the form of pain or tightness and, due to the fact that many patients with affective and anxiety disorders report this experience, anxiety thus became the target of great clinical concern.

METHODS

Participants

The sample was made up of 100 patients treated in the general, anxiety and adult affective disorders outpatient clinic of the Institute of Psychiatry of the Hospital de Clínicas of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, with 35 patients belonging to the group with anguish 50 to the group without anguish and 15 to the doubt group, that is, the group of patients who declared the experience of anguish but could not describe it precisely.

Measures

Sociodemographic questionnaire. Developed with the objective of collecting information regarding the demographic and sociocultural variables of the participants, namely, Age (years), Gender (Male, Female, Other); Education level (Complete Higher Education, Incomplete Higher Education, Complete Secondary Education, Incomplete Secondary Education, Complete Primary Education, Incomplete Primary Education; Marital Status (Single, Married, Divorced, Widowed, No Answer).

BSI (Brief Inventory of Psychopathological Symptoms). This inventory evaluates psychopathological symptoms related to nine different dimensions and culminates in a summary evaluation consisting of three Global Indices. The nine dimensions as follows: Somatization: includes items 2, 7, 23, 29, 30, 33 and 37; Obsessions-Compulsions: includes items 5, 15, 26, 27, 32, 36; Interpersonal sensitivity: includes items 20, 21, 22 and 42; Depression: includes items 9, 16, 17, 18, 35, 50; Anxiety: includes items 1, 12, 19, 38, 45, 49; Hostility: includes items 6, 13, 40, 41 and 46; Phobic Anxiety: includes items 8, 28, 31, 43 and 47; Paranoid Ideation: includes items 3, 14, 34, 44 and 53; Psychoticism: includes items 3, 14, 34, 44 and 53.

DSQ-40 (Defense Styles Inventory) Ego defense mechanisms, which is a psychoanalytic concept, have been defined as an indication of how individuals deal with conflict (5). The defensive style is considered an important dimension of the personality structure of the individual and became the first psychoanalytic concept recognized by the DSM-IV13 as a guide for future research (6).

HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale). The HADS is divided into two subscales: the anxiety subscale (tension or contraction, fear, worry, difficulty relaxing, butterflies or tightness in the stomach, restlessness, panic) – HADS-A and the depression subscale (anhedonia, difficulty finding humor when seeing funny things, deep sadness, slowness in thinking and performing tasks, loss of interest in taking care of one’s appearance, hopelessness, lack of pleasure when watching television programs, radio or reading something) – HADS- D. Both contain seven items interspersed between questions regarding anxiety and depression. The factors and their corresponding items are shown below: Anxiety symptoms: items: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13. Depression symptoms: items: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 All items are classified on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. Through these defined values, the HADS subscales can indicate the presence of anxiety or depression disorders at different levels: 0-7, normal; 8-10, light; 11-14, moderate; 15-21, serious. This scale, after studies and validation for the Brazilian population and the Portuguese language, has been widely used. The questionnaire is self-administered, and the evaluated subject can count on the help of the evaluator, who in the case of this work was always the same, if he did not understand the content of some questions.

HAM-A (Hamilton Anxiety Scale). The HAM-A contains fourteen items distributed in two groups, the first group with seven items related to symptoms of anxious mood; Insomnia; depressed mood: loss of interest, mood swings, depression, early awakening;) and the second group, also composed of seven items, related to the physical symptoms of anxiety (motor somatization; sensory somatization; cardiovascular symptoms; respiratory symptoms; gastrointestinal symptoms; genitourinary symptoms and neurovegetative symptoms).

STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory). The STAI is a self-report scale that depends on the subject’s conscious reflection in the process of evaluating their anxiety state, as well as their personality characteristics. State anxiety scores can vary in intensity over time, are limited to a particular moment or situation, and individuals with state anxiety tend to become anxious only in particular situations (7). It is characterized by unpleasant feelings of tension and apprehension, consciously perceived, and can vary in intensity, depending on the danger perceived by the person and the change over time. Trait anxiety refers to relatively stable individual differences in the tendency to react to situations perceived as threatening with increases in the intensity of the anxiety state. It has a lasting characteristic in the person because the personality trait is less sensitive to environmental changes and because these remain relatively constant over time.

MINI (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview). The MINI was developed by researchers at the PitiéSalpêtrière Hospital in Paris and the University of Florida in the United States and consists of a brief questionnaire lasting 15-30 minutes, compatible with the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-III-R and ICD-10 (different versions), which can be used by doctors after a quick training (1h to 3h). The MINI is organized into independent diagnostic modules, designed to optimize the sensitivity of the instrument, despite a possible increase in false positives. Two versions of the MINI were developed to address the specific diagnostic objectives of different contexts of use: 1) intended primarily for use in primary care and clinical trials, the MINI comprises 19 modules exploring 17 DSM-IV Axis I disorders, Suicide Risk and Antisocial Personality Disorder.

Procedure

While waiting for care, patients were invited to participate in the research, received an explanation about its objective and signed the Free and Informed Consent Form. Patients responded to a Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) diagnostic instrument containing the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for anxiety disorders and affective disorders and a questionnaire to identify the presence of anguish. Additionally, patients were asked to answer the Brief Inventory of Psychopathological Symptoms (BSI), the Defense Styles Inventory (DSQ-40), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM -A) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Patients were also asked to record a statement about the experience of anguish. This recording was listened to and analyzed to determine whether the patients were experiencing anguish or not.

The statistical analysis included two phases: descriptive analysis and inferential analysis. In the scope of descriptive analysis, the first step consisted of comparing the groups with and without anguish with numerical and categorical variables. The second stage consisted of examining the variables of the questionnaires. In the third stage, a correspondence analysis was carried out to visually investigate possible associations between anguish, depression and anxiety. The fourth stage included the comparison of the anxiety and depression symptoms most associated with anguish. The fifth stage of the descriptive analysis focused on a sensitivity analysis, which consisted of relocating the doubt group to the anguish group to investigate changes in the interpretations of the results of the comparison of the anguish variable with the MINI Anxiety and the MINI Depression. The inferential analysis consisted of two stages. The first stage focused on reducing the size of some questionnaires and constructing more discriminative latent variables in relation to groups with and without anguish. In the second stage, the variables with the greatest predictive power for discomfort were identified.

RESULTS

The first stage of the descriptive analysis consists of comparing the groups with distress and without distress with numerical and categorical variables. Tables were created with a descriptive summary of the quantitative variables and the frequencies and percentages of qualitative variables in the groups with distress, without distress and doubt. Also, graphs were created to facilitate data visualization. In the context of comparing the groups with distress and without distress with the numerical variables, it was concluded that only the variable BSI Somatization was considered significant and, among the categorical variables, the variables that presented the greatest significance were the variables gender, level of education, HAM- A Fears, HAM-A Depressive Mood, HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms and HAM-A Neurovegetative Symptoms (Table 1-2).

Table 1. Comparison of groups with anguish and without anguish with numerical variables using the Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney test.

| Variable | P-value | |

| Age | 0.248 | |

| BSI Somatization | 0.02* | |

| BSI Obsession Compulsion | 0.926 | |

| BSI Interpersonal Sensitivity | 0.828 | |

| BSI Depression | 0.724 | |

| BSI Anxiety | 0.72 | |

| BSI Hostility | 0.571 | |

| BSI Phobic Anxiety | 0.684 | |

| BSI Paranoid Ideation | 0.621 | |

| BSI Psicoticism | 0.71 | |

| HADS Anxiety | 0.828 | |

| HADS Depression | 0.504 | |

| IDATE State | 0.698 | |

| IDATE Trait | 0.761 | |

| HAM-A Total Score | 0.129 | |

| DSQ Antecipation | 0.682 | |

| DSQ Mood | 0.393 | |

| DSQ Supression | 0.45 | |

| DSQ Sublimation | 0.813 | |

| DSQ Racionalization | 0.898 | |

| DSQ Pseudo Altruísm | 0.734 | |

| DSQ Idealization | 0.351 | |

| DSQ Reactive Formation | 0.223 | |

| DSQ Anulation | 0.092 | |

| DSQ Projection | 0.647 | |

| DSQ Passive Agressin | 0.341 | |

| DSQ Acting Out | 0.775 | |

| DSQ IIsolation | 0.66 | |

| DSQ Desvalorization | 0.879 | |

| DSQ Autistic Fantasy | 0.796 | |

| DSQ Negation | 0.764 | |

| DSQ Displacement | 0.721 | |

| DSQ Dissociation | 0.539 | |

| DSQ Spin-off | 0.94 | |

| DSQ Somatization | 0.693 |

Table 2. Comparison of groups with anguish and without anguish with categorical variables via Chi-square test.

| Variable | P-value |

| Sex | 0.041* |

| Education level | 0.048* |

| Marital status | 0.592 |

| HAM-A Anxsious Mood | 0.953 |

| HAM-A Tension | 0.417 |

| HAM-A Fear | 0.003* |

| HAM-A Insomnia | 0.531 |

| HAM-A Intellectual Difficulties | 0.25 |

| HAM-A Depressed Mood | 0.049* |

| HAM-A Motor Somatizations | 0.885 |

| HAM-A Sensory Somatizations | 0.26 |

| HAM-A Cardiovascular Symptoms | 0.129 |

| HAM-A Respiratory Symptoms | 0.323 |

| HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms | 0.025* |

| HAM-A Genitourinary Symptoms | 0.924 |

| HAM-A Neurovegetative Symptoms | 0.018* |

| MINI Depression | 0.305 |

| MINI Anxiety | > 0.999 |

| MINI Other | 0.228 |

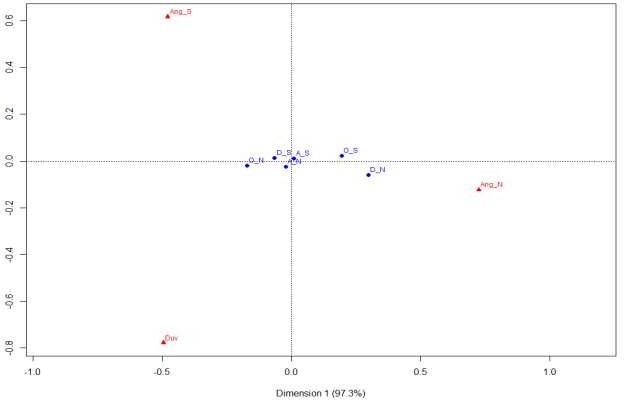

Anguish affects women more than men. The descriptive level of the Chi-Square test (p=0.041) also contributes to the evidence of this association between anxiety and gender. Regarding marital status, it was found that there were no notable differences between the groups, with the sample being mostly single people. There is an indication of the difference between the groups (p = 0.048), since the group without distress has a higher percentage of people with completed higher education. The mean and median age in the group with distress is lower, however, in the Wilcoxon Mann Whitney test, so the difference is not significant (p = 0.248). For the MINI questionnaire, the contingency tables that show the volumes of the MINI variables within the levels of the variable anguiish do not show a significant relationship between anguish and depression, anxiety or other diagnoses, a result that is reinforced by the Chi-square test. A correspondence analysis was also carried out for the MINI questionnaire to visually investigate possible associations of the groups formed by the contingency table composed of the variables anguish, MINI Anxiety, MINI Depression and MINI other diagnoses. It is observed that the group with depression (D_S) is closer to the group with anguish (Ang_S) than the group with anxiety (A_S), thus suggesting that anguish is more associated with depression than with anxiety. It is also noted that the group without depression (D_N) is close to the group without anxiety (Ang_N) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Correspondence analysis graphs between the variables Distress, MINI Depression, MINI Anxiety and MINI Other Diagnoses. Ang = Distress, A = Anxiety, D = Depression, O = Other Diagnoses, S = Yes, N = No.

Regarding the BSI questionnaire, only the distribution of the somatization variable was noticeably different between the groups. The median of the group with anguish is higher, in addition, the p-value of the Wilcoxon Mann Whitney test was significant (p = 0.020) (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive summary of the BSI Somatization variable in the doubt, no anguish and anguish groups.

| Group | N | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

| Anguish | 39 | 12.6 | 6.19 | 1 | 13 | 23 |

| No Anguish | 46 | 9.5 | 6.39 | 0 | 8.5 | 24 |

| Doubt | 15 | 14.1 | 8.3 | 0 | 13 | 24 |

| Total | 100 | 11.4 | 6.81 | 0 | 11 | 24 |

SD: Standard deviation.

As for the DSQ-40, no ego defense mechanism appears to be related to anxiety. Wilcoxon Mann Whitney tests also did not indicate significant differences. In relation to the HADS, for both anxiety and depression, no evidence was found regarding a pattern of association with anguish. Regarding the HAM-A, the variables fears, depressive mood, gastrointestinal symptoms and neurovegetative symptoms showed significant differences for the variable anguish (individual significance level, Cronbach’s α of 0.05), with the group with anguish being the one with the highest values of punctuation (Table 4-7).

Table 4. Distribution of frequencies and percentages of the HAM-A variable Fears in the groups doubt, without anguish and with anguish.

| HAM-A Fears | Group | |||

| Doubt | No Anguish | Anguish | Total | |

| 0 | 3 (20.0%) | 19 (41.3%) | 9 (23.1%) | 31 (31.0%) |

| 1 | 2 (13.3%) | 12 (26.1%) | 6 (15.4%) | 20 (20.0%) |

| 2 | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (6.5%) | 15 (38.5%) | 20 (20.0%) |

| 3 | 2 (13.3%) | 5 (10.9%) | 7 (17.9%) | 14 (14.0%) |

| 4 | 6 (40.0%) | 7 (15.2%) | 2 (5.1%) | 15 (15.0%) |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 46 (100%) | 49 (100%) | 100 (100%) |

Table 5. Distribution of frequencies and percentages of the HAM-A variable Depressive Mood in the groups doubt, without anguish and with anguish.

| HAM | Group | |||

| Depressed Mood | Doubt | No Anguish | Anguish | Total |

| 0 | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.7%) | 3 (7.7%) | 7 (7.0%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.7%) | 6 (15.4%) | 10 (10.0%) |

| 2 | 4 (26.7%) | 10 (21.7%) | 6 (15.4%) | 20 (20.0%) |

| 3 | 4 (26.7%) | 14 (30.4%) | 21 (53.8%) | 39 (39.0%) |

| 4 | 7 (46.7%) | 14 (30.4%) | 3 (7.7%) | 24 (24.0%) |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 46 (100%) | 49 (100%) | 100 (100%) |

Table 6. Distribution of frequencies and percentages of the variable HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms in the groups of doubt, without and with anguish.

| HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms | Group | |||

| Doubt | No Anguish | Anguish | Total | |

| 0 | 2 (13.3%) | 22 (47.8%) | 6 (15.4%) | 30 (30.0%) |

| 1 | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (8.7%) | 8 (20.5%) | 13 (13.0%) |

| 2 | 5 (33.3%) | 12 (26.1%) | 12 (30.8%) | 29 (29.0%) |

| 3 | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (10.9%) | 8 (20.5%) | 18 (18.0%) |

| 4 | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (6.5%) | 5 (12.8%) | 10 (10.0%) |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 46 (100%) | 49 (100%) | 100 (100%) |

Table 7. Distribution of frequencies and percentages of the HAM-A variable Neurovegetative Symptoms in the groups doubt, without and with anguish.

| HAM-A Neurovegetative Symptoms | Group | |||

| Doubt | No Anguish | Anguish | Total | |

| 0 | 0 (0%) | 18 (39.1%) | 5 (12.8%) | 23 (23.0%) |

| 1 | 3 (20.0%) | 9 (19.6%) | 5 (12.8%) | 17 (17.0%) |

| 2 | 3 (20.0%) | 6 (13.0%) | 15 (38.5%) | 24 (24.0%) |

| 3 | 5 (33.3%) | 8 (17.4%) | 8 (20.5%) | 21 (21.0%) |

| 4 | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (10.9%) | 6 (15.4%) | 15 (15.0%) |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 46 (100%) | 49 (100%) | 100 (100%) |

As for the STAI questionnaire, both the trait STAI and the state STAI also showed no relationship between anxiety and anguish. In summary, the variables that showed the greatest relationship with distress were: gender, BSI somatization; HAM-A fears, depressed mood, gastrointestinal symptoms, and neurovegetative symptoms. No variable related to anxiety was associated with anguish in this first descriptive context. As for depression, only the HAM-A variable, “depressive mood”, was significant. An analysis to compare the symptoms of anxiety and depression (using the MINI as a diagnosis) most associated with anguish was also carried out to discover what symptoms the two disorders have in common with anguish. The Wilcoxon Mann Wtihney and Chi-square tests show the association between the other variables and each of the three mentioned. Between anguish and depression, the variables BSI Somatization and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms were considered significant, and between anguish and anxiety, only the HAM-A variable fears was significant (Table 8-9).

Table 8. Significance comparative table.

| Variable | Anguish (P-value) | Anxiety (P-value) | Depression (P-value) |

| BSI Somatization | 0.02 * | 0.826 | 0.001* |

| BSI Obsession Compulsion | 0.926 | 0.02 * | 0.001* |

| BSI Interpersonal Sensitivity | 0.828 | 0.023 * | 0.008* |

| BSI Depression | 0.724 | 0.407 | 0.001* |

| BSI Anxiety | 0.72 | 0.032 * | <0.001* |

| BSI Hostility | 0.571 | 0.208 | <0.001* |

| BSI Phobic Anxiety | 0.684 | 0.024* | 0.001* |

| BSI Paranoid Ideation | 0.621 | 0.321 | 0.001* |

| BSI Psicoticism | 0.71 | 0.126 | 0.004* |

| DSQ Passive Aggression | 0.341 | 0.069 | 0.049* |

| DSQ Acting Out | 0.775 | 0.313 | 0.019* |

| DSQ Dissociation | 0.539 | 0.002* | 0.949 |

| DSQ Somatization | 0.693 | 0.015* | 0.04* |

| HADS Anxiety | 0.828 | 0.03* | 0.015* |

| HADS Depression | 0.504 | 0.224 | 0.005* |

| IDATE Trait | 0.761 | 0.002* | 0.002* |

| HAM-A Total | 0.129 | 0.065 | 0.003* |

Table 9. Comparative table of the significance (Chi-square test) of symptoms and defense mechanisms of anguish with those of anxiety and depression.

| Variable | Anguish (P-value) | Anxiety | Depression |

| (P-value ) | (P-value) | ||

| HAM-A Anxious Mood | 0.953 | 0.054* | 0.625 |

| HAM-A Tension | 0.417 | 0.15 | 0.043* |

| HAM-A Fears | 0.003* | 0.03* | 0.184 |

| HAM-A Depressed Mood | 0.049* | 0.231 | 0.084 |

| HAM-A Respiratory Symptoms | 0.323 | 0.132 | 0.029* |

| HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms | 0.025* | 0.444 | 0.946 |

| HAM-A Neurovegetative Symptoms | 0.018* | 0.494 | 0.023* |

| MINI Depression | 0.305 | 0.28 | – |

| MINI Anxiety | > 0.999 | – | 0.28 |

| MINI Other | 0.228 | > 0.999 | 0.588 |

The inferential analysis consisted of three steps. The first stage focuses on reducing the size of some questionnaires and the construction of latent variables, possibly more discriminative in relation to groups without distress and distress, and for this purpose the Item Response Theory was used. The second stage aims to identify which variables have the greatest predictive power for anguish. Item Response Theory (IRT) was used to reduce the size of the HAM-A and DSQ-40 questionnaires. For HAM-A, two scores were generated through IRT. The first (Hamilton TRI Score) was applied to all 13 variables, the second (Reduced Hamilton TRI Score) was applied only to the most significant variables for distress in the Chi-square tests and also of interest to the researcher, namely: HAM -A Fears, HAM-A Depressive Mood, HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms and HAM-A Neurovegetative Symptoms. Two Scores were also constructed by simple sum: HAM-A Sum Score and HAM-A Reduced Sum Score, the latter being constructed by the variables mentioned above. Figure 12 shows the percentile graph of the HAM-A TRI score and HAM-A Sum score variables for the groups without and with anguish. It is possible to see two points by observing the graphs. The first is that the HAM-A questionnaire actually has a relationship with the variable anguish, the second is that the difference between the two methods is clear, in which the IRT proved to be superior to the simple sum in terms of discriminatory power. of the groups. The DSQ-40 has 3 latent variables according to the literature: Neurotic DSQ, Immature DSQ and Mature DSQ, which are described in the section dedicated to the description of the variables. The DSQ, both via the sum and via the TRI, appears to have no relationship between the groups with and without anguish. To investigate whether anguish is more related to depression than to anxiety, a logistic regression model was adjusted in which the response variable (dependent) was defined as having or not having anguish depending on many independent variables considered in the study. The model was adjusted without the doubt group, therefore, for 85 observations, with the variable distress being the response variable and the following 23 explanatory variables: DSQ-40 mature TRI score; immature DSQ-40 TRI score; TRI neurotic DSQ-40 score; reduced Hamilton score TRI; IDATE State; IDATE Trait; MINI depression; MINI anxiety; MINI other diagnosis; BSI somatization; BSI obsession compulsion; BSI depression; BSI anxiety; BSI hostility; BSI phobic anxiety; BSI paranoid ideation; BSI psychoticism; BSI interpersonal sensitivity; HADS anxiety; Age; Gender; Education level; Marital status. The selected variables were the following: Gender, Reduced Hamilton Score, BSI Somatization, BSI Hostility, BSI Obsession Compulsion, Age and MINI Depression (Table 10-11).

Table 10. Estimates of the coefficients of the Logistic Regression model.

| Parameters | Stimate | Standard Error | P-value |

| Intercept | 2.7809 | 1.359 | 0.041 |

| MINI Depression (Ref.- Without depression) | 1.294 | 0.773 | 0.094 |

| BSI Somatization | 0.09 | 0.052 | 0.086 |

| Age | -0.044 | 0.018 | 0.013 |

| Score HAM-A TRI Reduced | 1.047 | 0.419 | 0.013 |

| BSI Hostility | -0.143 | 0.067 | 0.033 |

| BSI Obsession Compulsion | -0.118 | 0.065 | 0.07 |

| Sex (Ref.– Male) | 1.016 | 0.586 | 0.083 |

Table 11. Odds ratios of the logistic regression model with respective 95% confidence intervals.

| Variable | Reference | Stimate (RC) | Confiance (95%) |

| MINI | No depression | 3.64 | [0.843 ; 18.363] |

| BSI Somatization | 1 point increase | 1.094 | [0.989 ; 1.219] |

| Age | 1 point increase | 0.956 | [0.921 ; 0.989] |

| Score HAM-A TRI Reduced | 1 point increase | 2.849 | [1.297 ; 6.856] |

| BSI Hostility | 1 point increase | 0.866 | [0.753; 0.982] |

| BSI Obsession Compulsion | 1 point increase | 0.888 | [0.776 ; 1.001] |

| Sex | Male | 2.763 | [0.897 ; 9.165] |

Higher BSI Somatization scores are also associated with greater chances of having anguish, with each increase of one point in this domain the chance of anguish increases by 9.4%, keeping the other variables fixed. A 1-year increase in age reduces the expected chance of experiencing anguish by 4.6%, keeping other variables constant. The higher the HAM-A Score, the greater the expected chance of having anguish, that is, with each increase of one point in this Score there is an increase in the expected chance of anguish of 185%, considering the other variables in the model constant. For BSI Hostility, for each increase of 1 point, the expected chance of experiencing anguish decreases by 15.5%, keeping the other variables fixed. For BSI Obsession Compulsion, with each increase of 1 point, the chance of having anguish decreases by 12.6%, keeping the other variables fixed. The expected chance of women experiencing anguish is greater compared to men (the chance for women is 2.76 times greater than that for men), considering other variables constant. The estimates obtained indicate that the expected chance of people with depression experiencing anguish is greater in relation to those who do not present this symptom (the chance for people with depression is 3.64 times greater in relation to people without depression), keeping the other variables in mind. fixed.

DISCUSSION

The main objectives of this investigation were to prove the hypotheses that there are differences in symptomatology and comorbidities regarding the experience of anguish, and that anguish is more linked to depression than to anxiety. Based on the first hypothesis, it was concluded that the symptoms that are most linked to anxiety are: BSI somatization, HAM-A fears, HAM-A depressed mood, HAM-A gastrointestinal symptoms and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms. Regarding the second hypothesis, it appears that of the 82 patients with depression, 87.2% had anguish, while of the 69 patients with anxiety, 69.2% had distress, indicating a higher frequency of distress among patients with depression.

Regarding the hypothesis of differences in symptoms and comorbidities between patients with distress and patients without distress, we can verify that the experience of distress is related to somatic symptoms that include thoughts and emotional states in conflict and that cause pain in the body such as aches and pains. head, back and chest, stiffening of the limbs, tachycardia, among others. Among patients who experienced distress, chest pain was the most frequent somatic symptom. Regarding the variables of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale that showed significance, a significant relationship was noted between the variable HAM-A depressed mood and the variables HAM-A gastrointestinal symptoms and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms with regard to the experience of anguish. Another variable from the Hamilton Anxiety Scale that proved to be significant between patients with anguish and patients without anguish was the HAM-A fear variable. Since patients who reported the experience of anxiety complained of pain or tightness in the chest region, main characteristics of anguish, fear in this context is not fear of a specific object, such as an animal, natural environment or specific situation., but rather the fear of dying due to the experience of anguish. According to Assumpção Júnior (8) anguish is more related to the fear of sudden death. In relation to the gastrointestinal and neurovegetative symptoms which, together with the depressed mood symptom which proved to be significant in the context of the experience of anguish, the first involve problems that are related to the anguish, namely the burning sensation or heartburn, abdominal fullness, nausea and vomiting, while among the neurovegetative symptoms, the problems that are more related to distress include pain, malaise, discomfort, burning, heaviness, tightness, swelling or distension in a specific organ, which in this case is the chest region . The Hamilton Anxiety Scale was also subjected, based on the application of Item Response Theory to dimensionality reduction to find more interesting properties than the simple sum of correct answers and it was concluded that, after dimensionality reduction, i.e. after selecting the HAM-A variables that are most related to anguish, these appear to be more significant compared to the simple sum of correct answers, indicating that, especially the variables HAM-A depressed mood, HAM-A fears, HAM -A gastrointestinal symptoms and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms have significance regarding the experience of distress. The greater significance of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale variables, as well as the BSI somatization variable, is also proven with the application of the Binomial Logistic Regression Model, which serves to select the independent variables and predict which group a patient is more likely to belong to. based on the independent variables.

As for the second hypothesis, which concerns the greater frequency of anguish among patients with depression compared to patients with anxiety, this can be proven based on the statements given by patients, which refer more to depression than to anxiety. Anxiety is a feeling that causes bodily sensations such as tightness in the chest in situations that occur in the present moment, and the vast majority of patients declared having experienced anguish in present moments, such as loneliness, death of relatives, divorce, unemployment, high workload. work, difficulties in carrying out a task, sadness and thoughts about suicide, fear and insecurity, hopelessness, loss of control, problems related to work, family differences, despair, difficulty crying, physical illnesses, depression, travel, lack of emotional control, sad news, disappointments, bullying, parental rejection, political problems, feelings of oppression, crises due to psychiatric illnesses, stress, emotional pressure, accidents in the family, among others. Another result that reinforces the relationship between anguish and depression is given by the comparative analysis of significance, whose objective was to verify which variables are in common between anguish and depression and between anguish and anxiety, in which it was found that between anguish and depression, the common variables were BSI somatization and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms, while between anguish and anxiety, only the HAM-A fear variable was common. This result reinforces the theory that anguish is more related to depression than to anxiety, since anguish is a feeling that encompasses somatic manifestations, reaching the conclusion that it is a visceral and physical feeling, while anxiety is a more psychic feeling. Based on the binomial logistic regression model, it is also possible to verify the greater significance among patients with depression compared to patients with anxiety regarding the experience of anguish, in which it can be concluded that, after applying the model, patients with depression have 3 .64 more likely to experience anguish than patients with anxiety. The biblical accounts also follow the direction of the relationship between anguish and depression, since the characters mentioned in the introduction to this research experienced, in addition to anguish, loneliness, fear, the desire to die and psychological suffering, that is, symptoms linked to depression.

Another result indicating a greater relationship between anguish and depression than between anguish and anxiety concerns gender, in which it is found that anguish has a greater presence in females, despite the sample being made up mostly of women. However, judging by the proportion of women and men who experienced anguish, it can be concluded that anguish exerts greater force among women. The relationship between the higher prevalence of anguish among females and depression is justified by the higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among women, since data indicates that women have twice as much depression as men and try twice as much to suicide. According to data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health, depression affects 14.7% of women, while men are affected by 7.3%.

Future research can also stimulate conceptual analysis in the areas of psychiatry, psychology and other areas that are related to psychopathology, particularly that related to neurosciences, since the use of complex concepts in basic research, without their prior analysis, becomes sterile, which may be one of the causes for the scarce results in translational studies in psychopathology/neurosciences. It is also recommended that research be carried out with a larger database, as well as using more accurate strategies for diagnosing anguish that provide greater precision in analyzes and greater discrimination of groups with and without anguish and respective predictors.

In summary, the present study suggests that the variables that were most related to anxiety were: gender, reduced HAM-A score, BSI somatization, BSI hostility, BSI, obsession-compulsion, age and MINI depression. The inferential analysis showed evidence towards the main hypothesis of the investigation: “Depression is more related to anguish than anxiety”. It is worth highlighting the selection of the variable MINI depression using the stepwise method, which showed a significant association (at a level of 10%), with the interpretation that people with depression are more likely to experience distress compared to people who do not have depression. However, in the selection of variables most associated with distress, no variable related to anxiety was statistically associated with distress, with the exception of the domains of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale.

The variables that showed the most relationships with anxiety are the following: Gender, Reduced HAM-A Score, BSI Somatization, BSI Hostility, BSI Obsession Compulsion, Age and MINI Depression.

The inferential analysis showed evidence towards the main hypothesis of the study: “Depression is more related to anguish than anxiety”. It is worth highlighting the selection of the MINI Depression variable using the stepwise method, which showed a significant association (at a level of 10%), with the interpretation that people with depression are more likely to experience anguish compared to people who do not have depression. However, in the selection of variables most associated with anguish, no variable related to anxiety was statistically associated with anguish, with the exception of domains from the HAM-A questionnaire.

The present study suffers from some limitations. First, socioeconomic status or ethnicity are not measured, but to our knowledge, they have not previously been associated with the experience of distress. Secondly, the Portuguese version of the Psychopathological Symptom Inventory was used to the detriment of the lack of validation of this scale for the Brazilian population.

Future studies are recommended with a larger database as well as a more accurate strategy for diagnosing anguish, which could bring greater precision to the analyzes and allow greater discrimination of groups with and without anguish and their predictors.

CC BY Licence

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

REFERENCES

- Szuhany KL, Otto MW. Assessing BDNF as a mediator of the effects of exercise on depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;123:114-118. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.02.003

- López-Ibor J. Psychiatric causes of chest pain. In: Diaz-Rubio M, Macaya C, López-Ibor J (eds) Dolor Thorácico Incierto. Madrid: Fundación Mutua Madrilena. 2007.

- Freud S. The psychic mechanisms of hysterical phenomena. In: Brazilian Standard Edition of Complete Psychological Works, v. 3. Rio de Janeiro: Imago, 1893/1996.

- Gentil V, Gentil ML. Why anguish?. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(1):146-147. doi:10.1177/0269881109354134

- Gallani MC, Proulx-Belhumeur A, Almeras N, Després JP, Doré M, Giguère JF. Development and Validation of a Salt Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ-Na) and a Discretionary Salt Questionnaire (DSQ) for the Evaluation of Salt Intake among French-Canadian Population. Nutrients. 2020;13(1):105. Published 2020 Dec 30. doi:10.3390/nu13010105

- Scaini CR, Vieira IS, Machado R, et al. Immature defense mechanisms predict poor response to psychotherapy in major depressive patients with comorbid cluster B personality disorder. Braz J Psychiatry. 2022;44(5):469-477. doi:10.47626/1516-4446-2021-2214

- Knowles KA, Olatunji BO. Specificity of trait anxiety in anxiety and depression: Meta-analysis of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;82:101928. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101928