Özer İşisağ1

1 Department of Prosthodontics, Afyonkarahisar University of Health Sciences Faculty of Dentistry, Afyonkarahisar, Türkiye

Received: 13 April 2024

Revised: 16 April 2024

Accepted: 16 April 2024

Published: 16 April 2024

ABSTRACT

| This study aimed to assess the impact of adding zirconium oxide nanoparticles at different weight ratios on the flexural strength of bis-acrylic composite resin used in provisional restorations. A total of 36 bis-acryl composite resin samples (25x2x2 mm) were used in this study. The samples were divided into four groups: a control group without any addition of nanoparticles (n=9) and three experimental groups with 1%, 2%, and 5% by weight of zirconium oxide nanoparticles (nine samples for each group). After polymerisation, the surface of all samples was standardised, cleaned in an ultrasonic cleaner, and kept in distilled water at 37°C for 24 hours. Subsequently, a three-point bending test was carried out on all samples. Additionally, scanning electron microscope images of the fracture zone of one sample from each group were analysed. The highest flexural strength was observed in the group with 1 wt% zirconium oxide nanoparticles added, and a statistically significant increase was observed compared to the control group. The other groups did not exhibit a statistically significant difference compared to the control group. In the SEM images, the groups containing 2% and 3% zirconium oxide nanoparticles by weight showed similar features. However, the 1% added group had a different surface topography. After adding 1 wt% zirconia nanoparticles, bis-acrylate composite resins exhibited the highest flexural strength. As a result, they can be safely used in temporary restorations. |

Keywords:

Zirconium oxide; nanoparticles; flexural strength; temporary dental restoration.

Cite as: İşisağ Ö. Effect of Zirconium Oxide Nanoparticles on the Flexural Strength of Bis-Acryl Composite Resins for Temporary Fixed Restorations: An In Vitro Study. Acta Med Eur. 2024;6(3):12-16. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10980331

INTRODUCTION

Temporary restorations play a crucial role in fixed dental prostheses. They have three primary requirements: mechanical, biological, and aesthetic. These restorations perform several functions, such as protecting the pulp, maintaining occlusal function, and enhancing appearance. Moreover, interim restorations also help evaluate the effectiveness of treatment and assess prosthetic form and function (1–3). These restorations can be made from various materials, including polyvinylethylmethacrylate, urethane methacrylate, polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) and bis-acrylic composite resins (BA). PMMA resins are cost-effective but have limitations in mechanical properties. BA is preferred for mock-ups and interim restorations because of their ease of use, low polymerisation contraction, and satisfactory aesthetics (4–6). When selecting a temporary restoration material for dental procedures, it is essential to consider its physical and mechanical properties. A failed temporary restoration can lead to discomfort and financial loss, requiring repair or replacement of the restoration. Researchers have tried incorporating particles, wires or fibres to improve the mechanical properties of dental materials. By adding nanoparticles to polymers, high-performance materials can be created. The mechanical properties of such materials depend on several factors, including particle size, polymer-particle interfaces, manufacturing techniques, and consistency of particle dispersion. Zirconia (ZrO2) nanoparticles effectively improve dental materials by providing high hardness and biocompatibility. Incorporating ZrO2 nanoparticles during manufacturing enhances particle uniformity, producing better quality materials (6–10). Numerous researches have demonstrated that incorporating ZrO2 particles into dental materials enhances properties, including hardness and flexural strength (11–13). However, no study has been found so far that investigates the influence of ZrO2 particles on the mechanical strength of BA. Therefore, this study aims to examine the effect of adding ZrO2 particles at different ratios on the flexural strength of BA. The study’s null hypothesis states that adding ZrO2 particles at different ratios would not affect BA’s flexural strength.

METHODS

The materials and devices used in the study are shown in Table 1. A total of 36 specimens were produced and separated into two groups: A control (CTR) (n=9) and an experimental group (n=27). The experimental group was divided into three subgroups according to the amount of ZrO2 added (1% added: BA-1, n=9; 2% added: BA-2, n=9; 5% added: BA-5, n=9). All specimens were bar-shaped and had dimensions of 25mm x 2mm x 2mm.

The base and catalyst of the BA resin were weighed equally using a precision balance. Then, ZrO2 powder was added in varying amounts of 1%, 2%, and 5% of the total weight of the mixture. A single operator manually mixed the base, catalyst, and ZrO2 powder. The mixture was transferred to a plastic mould immediately without being polymerised. The mould was pressed from the top and bottom with two glasses, and the mixture was allowed to polymerise. After polymerisation, the samples were removed from the mould and any edge irregularities were corrected using tungsten carbide burs. To standardise all specimens, a single operator sanded all surfaces of the specimens with silicon carbide sandpapers of 600, 800, 1000, and 1200 grit, respectively. Once sanded, the samples were ultrasonically cleaned in ethyl alcohol for 15 minutes. The specimens were then stored in distilled water at 37°C for 24 hours before undergoing a 3-point bending test using a universal testing machine. SEM images were taken at 500 and 3000 magnifications to examine the fracture surface of a sample from each group after completing the fracturing process.

Table 1. Materials and devices used in the study.

| Materials and devices | Brand, Manufacturer |

| Bis acryl composite resin | Primma art, FGM DENTAL GROUP |

| 40 nm zirconium dioxide (3Y-TZP) | Ytrria -Zirconia, Nanografi |

| 0.01 g precision balance | FLY 300, Necklife |

| 2mm x 2mm x 25mm mould | N/A |

| Incubator | Nüve EN055, Nüve |

| Ultrasonic cleaner | VEVOR, N/A |

| #600, #800, #1000 and #1200 silicon carbide abrasive papers | N/A |

| Universal test machine | MIN-100, Moddental |

Descriptive statistics of the continuous variables were presented with mean and standard deviation values. The normality of continuous variables was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The One-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test were used to compare continuous variables, and p < 0.05 was set as the level of statistical significance.

RESULTS

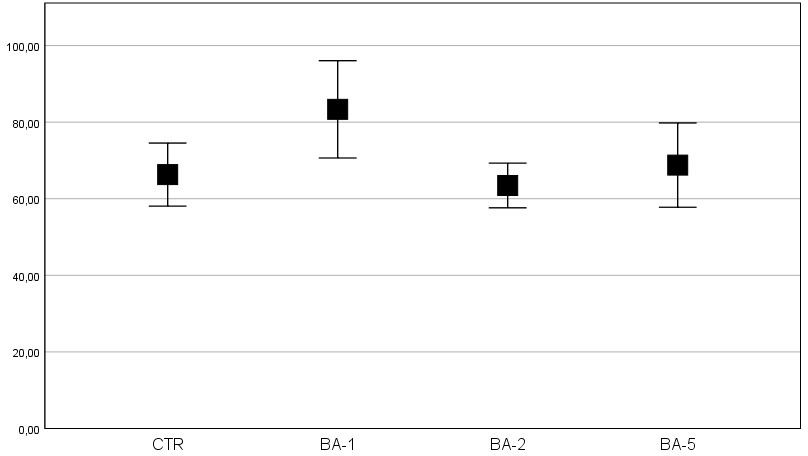

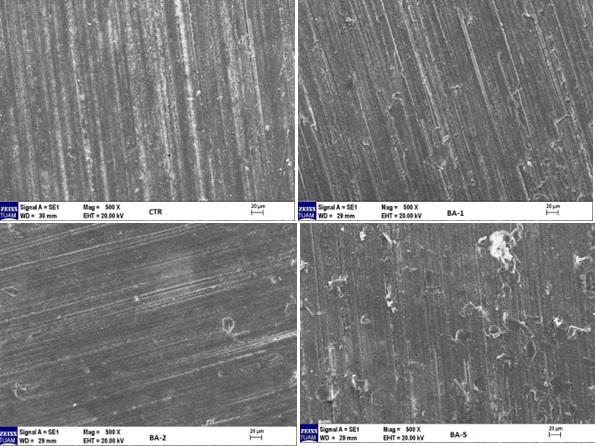

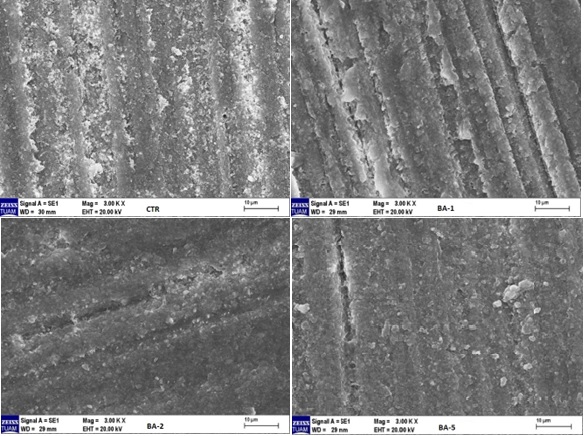

Table 2 and Figure 1 show the flexural strength mean and standard deviation values. The BA-1 group had the highest flexural strength, while the lowest was found in the BA-2 group. After conducting one-way ANOVA, a significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed between the mean values (Table 3). The Tukey test showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the BA-1 and CTR groups. Additionally, the mean flexural strength values indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the BA-1 and BA-2 groups, but no significant difference (p > 0.05) was observed between other groups. SEM images of a single specimen from each group analysed from the fracture zone have been presented in Figures 2 and 3. At a magnification of 3000, the BA-2 and BA-5 specimen images exhibit a comparable surface morphology. However, a distinct surface topography is observed in the BA-1 sample.

Table 2. Mean ±standard deviation (SD) flexural strength of pure BA (CTR) and ZrO2 and BA mixture.

| Groups | Mean±SD |

| Control | 66.30±10.71A |

| BA-1 | 83.34±16.52B |

| BA-2 | 63.46±7.59A |

| BA-5 | 68.78±14.31A.B |

Different uppercase letters in column identify significant differences (P<.05). BA:Bis-acryl composite resin, BA-1:1% added ZrO2, BA-2: 2% added ZrO2, BA-5: 5% added ZrO2. SD: Standard deviation, BA: Bis acryl.

Figure 1. Mean flexural strengths of the groups with 95% confidence intervals. CTR: Control, BA: Bis acryl.

Table 3. One way ANOVA results.

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

| Between Groups | 2115.603 | 3 | 705.201 | 4.336 | 0.01 |

| Within Groups | 5204.341 | 32 | 162.636 | ||

| Total | 7319.944 | 35 |

Figure 2. SEM image of one sample from each group at 500x magnification.

Figure 3. SEM image of one sample from each group at 3000x magnification.

DISCUSSION

In this study, ZrO2 nanoparticles were added to BA at different ratios, and the flexural strength of the prepared samples was evaluated. When the results were analysed, it was found that the flexural strength of the samples with 1 wt% ZrO2 nanoparticles was significantly higher than that of the control group, and the null hypothesis established at the beginning of the study was rejected.

Variations in the size of fillers in the structure of dental resins can reduce their effectiveness by creating porosity within the material. One study reported that crack propagation in BA occurs along the polymer matrix between the fillers in the material structure. ZrO2 nanoparticles show promise as filler additives for clinical use. Adding ZrO2 nanoparticles (≤5 wt%) increases the mechanical properties of dental materials, such as flexural strength, fracture toughness, hardness, and wear resistance (14,15). In this study, 1%, 2% and 5% by weight of ZrO2 nanoparticles were added to increase the flexural strength of BA. Nanoparticles can be added to the resin matrix as surface-modified or untreated particles. Both methods have favourable mechanical effects (16). In this research, no modification was applied to zirconium oxide nanoparticles.

The BA used in the study consists of a base and catalyst. In clinical practice, these two components are used with an automatic mixer, and the working time of the material starts after mixing in the automatic mixer. In this study, adding ZrO2 nanoparticles at specific ratios to the base and catalyst mixture is time-consuming, and the working time should be kept short. Therefore, the automatic mixer was not used during the study. Instead, equal amounts of base and catalyst by weight were manually added to a mixing paper to prevent them from coming into contact with each other. ZrO2 nanoparticles were added at 1%, 2% and 5% of the total mixture weight, and all components were mixed manually by a single operator until homogeneity was achieved. In a study to reinforce PMMA and BA with different fibre types, the base and catalyst of the BA were mixed using a similar method (17).

Flexural strength is a mechanical property commonly used to evaluate the strength and stiffness of interim resin materials. It becomes crucial when a long-span partial fixed prosthesis is required, or the interim restoration must endure masticatory forces for an extended period (18). To predict the clinical performance of dental materials over time, ageing techniques such as water storage are used under controlled laboratory conditions (19). In this study a 3-point flexural test was used to evaluate the mechanical strength of made of BA. In addition, the specimens were kept in an incubator at 37°C for 24 hours before the flexural strength was evaluated.

Nanoparticles improve dental biomaterials’ physical properties (20). One study reported that including SiO2 nanoparticles in low concentrations of temporary acrylic resin increased fracture toughness (21). In another study, 1%, 2.5% and 5% w/w ZrO2 nanoparticles were added to autopolymerising acrylic resin, and the flexural strength of the 1% ZrO2 nanoparticles group was significantly higher than the control group. At the same time, no significant difference was observed in the higher rate groups compared to the control group (20). As a result of this study, the average flexural strength value of the BA-1 group was statistically significantly higher than the control group. At the same time, no significant difference was observed in the BA-2 and BA-5 groups compared to the control group. This may be because a higher nanofiller concentration may reduce the load-carrying capacity of the polymer matrix, the poor adhesion between nanofiller and matrix is higher in materials with high nanofiller content, or the clustering of nanoparticles in the resin structure (16).

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images provide a detailed visual perspective on the study results. The similarity in the flexural strength values of samples BA-2 and BA-5 can be attributed to the comparable surface morphologies visible in the SEM images. The SEM images of the BA-2 and BA-5 specimens show aggregated ZrO2 nanoparticles, whereas the BA-1 sample had a different surface topography from the other experimental groups, and no nanoparticle accumulation was observed. Clustered nanoparticles can create localised stress areas and crack initiation (22). This may explain the higher flexural strength of the BA-1 group compared to the other groups.

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small and ZrO2 nanoparticles were not treated before adding to BA. The research was carried out with only three experimental groups without different proportions; the ageing processes were limited to water storage, the mechanical evaluations were limited to examining the flexural strength, and no other additional mechanical tests were carried out. In addition, optical and biological assessments were not performed, which are as essential parameters as mechanical strength. In the future, more comprehensive research can be carried out with a larger sample size, considering the above parameters.

The study’s results showed that the flexural strength of the control and experimental groups varied between 63 and 84 MPa. According to ADA ANSI Specification #27, the clinically acceptable flexural strength value for temporary restorative materials is 50 MPa. High flexural strength is essential for temporary restorative materials in the rehabilitation phase. From this point of view, BA with 1% ZrO2 nanoparticles can be safely used in temporary restorations.

Author contributions

Özer İşisağ: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation;; resources; supervision; writing—original draft.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any financial interest in the companies whose materials are included in this article.

ORCIDs:

OI: 0000-0002-2042-958X

REFERENCES

- Gantz L, Fauxpoint G, Arntz Y, Pelletier H, Etienne O. In vitro comparison of the surface roughness of polymethyl methacrylate and bis-acrylic resins for interim restorations before and after polishing. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;125(5):833.e1-833.e10. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.02.009

- Alshahrani FA, Gad MM, Al-Thobity AM, et al. Effect of treated zirconium dioxide nanoparticles on the flexural properties of autopolymerized resin for interim fixed restorations: An in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;130(2):257-264. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.09.031

- Gujjari AK, Bhatnagar VM, Basavaraju RM. Color stability and flexural strength of poly ( methyl methacrylate ) and bis acrylic composite based provisional crown and bridge auto polymerizing resins exposed to beverages and food dye : An in vitro study. 2013;24(2). doi:10.4103/0970-9290.116672

- Dds SBB, Freitas C De, Dds J, et al. Long-term stainability of interim prosthetic materials in acidic / staining solutions. 2020;32(1):73-80. doi:10.1111/jerd.12544

- Macedo MGFP, Volpato CAM, Henriques BAPC, Vaz PCS, Silva FS, Silva CFCL. Color stability of a bis-acryl composite resin subjected to polishing , thermocycling , intercalated baths , and immersion in different beverages. 2018;30(5):449-456. doi:10.1111/jerd.12404

- Alhavaz A, Dastjerdi MR, Ghasemi A, Ghasemi A. Effect of untreated zirconium oxide nanofiller on the flexural strength and surface hardness of autopolymerized interim fixed restoration resins. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2017;29(4):264-269. doi:10.1111/jerd.12300

- Zidan S, Silikas N, Haider J, Alhotan A, Jahantigh J, Yates J. Evaluation of Equivalent Flexural Strength for Complete Removable Dentures Made of Zirconia-Impregnated PMMA Nanocomposites. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(11):2580. doi:10.3390/ma13112580

- Singh A, Garg S. Comparative Evaluation of Flexural Strength of Provisional Crown and Bridge Materials-An Invitro Study. 2016;10(8):6-11. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/19582.8291

- Tribst JPM, Borges ALS, Silva-Concílio LR, Bottino MA, Özcan M. Effect of Restorative Material on Mechanical Response of Provisional Endocrowns: A 3D-FEA Study. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(3):649. doi:10.3390/ma14030649

- Zidan S, Silikas N, Al-Nasrawi S, et al. Chemical Characterisation of Silanised Zirconia Nanoparticles and Their Effects on the Properties of PMMA-Zirconia Nanocomposites. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(12):3212. doi:10.3390/ma14123212

- Alhareb AO, Ahmad ZA. Effect of Al2O3/ZrO2 reinforcement on the mechanical properties of PMMA denture base. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites. 2011;30(1):86-93. doi:10.1177/0731684410379511

- Barapatre D, Somkuwar S, Mishra SK, Chowdhary R. The effects of reinforcement with nanoparticles of polyetheretherketone , zirconium oxide and its mixture on flexural strength of PMMA resin. 2022;56(2):61-66. doi:10.26650/eor.2022904564

- Alshamrani A, Alhotan A, Kelly E, Ellakwa A. Mechanical and Biocompatibility Properties of 3D-Printed Dental Resin Reinforced with Glass Silica and Zirconia Nanoparticles: In Vitro Study. Polymers (Basel). 2023;15(11):2523. doi:10.3390/polym15112523

- Aati S, Akram Z, Ngo H, Fawzy AS. Development of 3D printed resin reinforced with modified ZrO2 nanoparticles for long-term provisional dental restorations. Dental Materials. 2021;37(6):e360-e374. doi:10.1016/j.dental.2021.02.010

- Knobloch LA, Kerby RE, Pulido T, Johnston WM. Relative fracture toughness of bis-acryl interim resin materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;106(2):118-125. doi:10.1016/S0022-3913(11)60106-6

- Alhavaz A, Rezaei Dastjerdi M, Ghasemi A, Ghasemi A, Alizadeh Sahraei A. Effect of untreated zirconium oxide nanofiller on the flexural strength and surface hardness of autopolymerized interim fixed restoration resins. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 2017;29(4):264-269. doi:10.1111/jerd.12300

- Kamble VD, Parkhedkar RD, Mowade TK. The effect of different fiber reinforcements on flexural strength of provisional restorative resins: An in-vitro study. Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics. 2012;4(1):1-6. doi:10.4047/jap.2012.4.1.1

- Kerby RE, Knobloch LA, Sharples S, Peregrina A. Mechanical properties of urethane and bis-acryl interim resin materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2013;110(1):21-28. doi:10.1016/S0022-3913(13)60334-0

- Zhang L xian, Hong D wei, Zheng M, Yu H. Is the bond strength of zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate lower than that of lithium disilicate? – A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthodont Res. 2022;66(4):530-537. doi:10.2186/jpr.JPR_D_20_00112

- Alshahrani FA, Gad MM, Al-Thobity AM, et al. Effect of treated zirconium dioxide nanoparticles on the flexural properties of autopolymerized resin for interim fixed restorations: An in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;130(2):257-264. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.09.031

- Topouzi M, Kontonasaki E, Bikiaris D, Papadopoulou L, Paraskevopoulos KM, Koidis P. Reinforcement of a PMMA resin for interim fixed prostheses with silica nanoparticles. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017;69:213-222. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.01.013

- Aati S, Akram Z, Ngo H, Fawzy AS. Development of 3D printed resin reinforced with modified ZrO2 nanoparticles for long-term provisional dental restorations. Dental Materials. 2021;37(6):e360-e374. doi:10.1016/j.dental.2021.02.010